The farm economy in the Tenth District continued to show signs of stabilizing in the third quarter of 2017, even as financial stress continued to build and income continued to decline. Although farm income was down from a year ago, the decrease was smaller than in recent years. Farmland values also continued to weaken, but only marginally. Although agricultural credit conditions continued to weaken, bankers indicated they do not expect the deterioration to lead to a sharp rise in asset liquidation.

Data

Credit Conditions | Fixed Interest Rates | Variable Interest Rates | Land Values

Farm Income

Farm income in the Federal Reserve’s Tenth District decreased in the third quarter, but at a slower rate. For the 13th consecutive quarter, a majority of bankers reported that farm income was lower than a year ago, but that the pace of the decline was less significant than recent quarters (Chart 1). In fact, only 52 percent of bankers reported that farm income had fallen from a year ago, the lowest share in two years. Moreover, slightly less than half of survey respondents expected farm income to decrease in the fourth quarter. Similarly, bankers expected capital and household spending in the farm sector to continue to decline in the third quarter, but also at a slower pace.

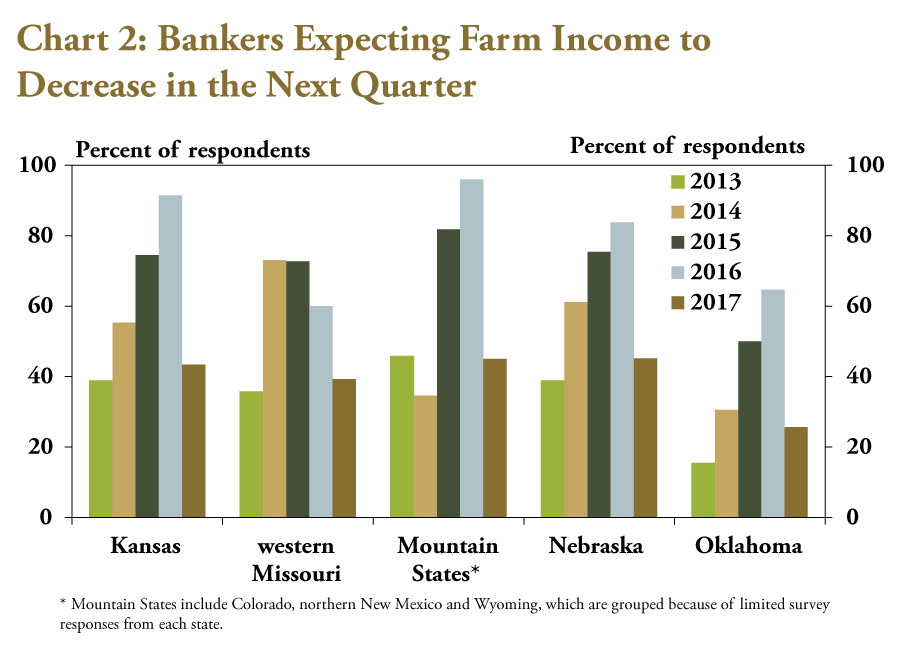

Expectations of future declines in farm income moderated throughout the District in the third quarter. The share of bankers expecting further declines in income in the fourth quarter was smaller than a year ago in each state (Chart 2). In western Missouri, a region where crop production has been very strong in recent years, the share of bankers expecting lower income next quarter decreased for a third straight year. Bankers in Kansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma also expected the decline in farm income to slow in the months ahead. In Oklahoma, a region that recently has improved alongside relatively strong livestock markets_, only 25 percent of bankers expected farm income to decline in the coming months.

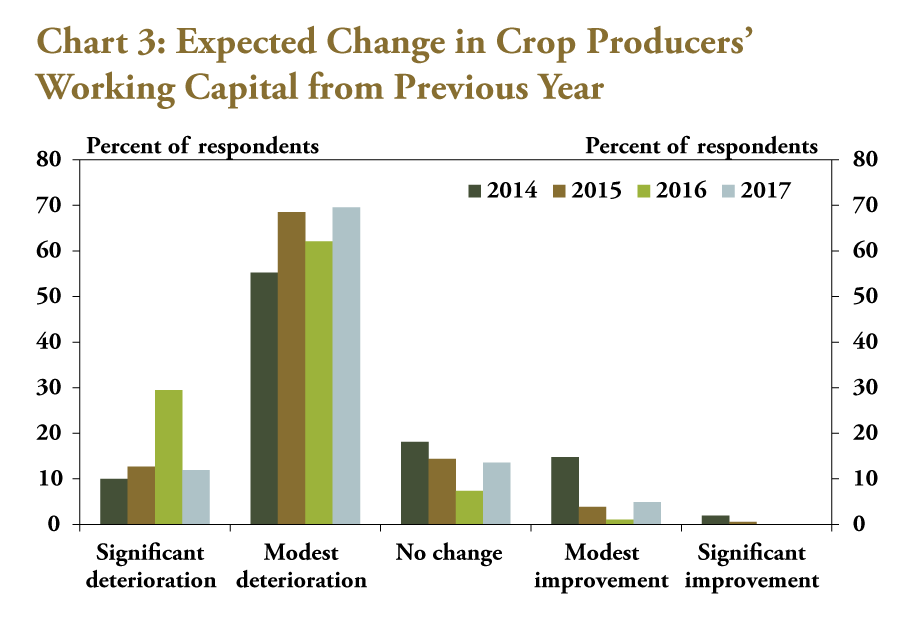

Although the pace of decline in farm income has moderated, the prolonged downturn in the District’s farm economy has continued to cut into the working capital of farm borrowers. Nearly 82 percent of bankers reported a year-over-year decline in crop producers’ working capital (Chart 3). Although the deterioration was less severe than in 2016, more bankers reported some deterioration in working capital in 2017 than in both 2014 and 2015. Less than 5 percent of bankers indicated working capital had improved in the third quarter.

Land Values

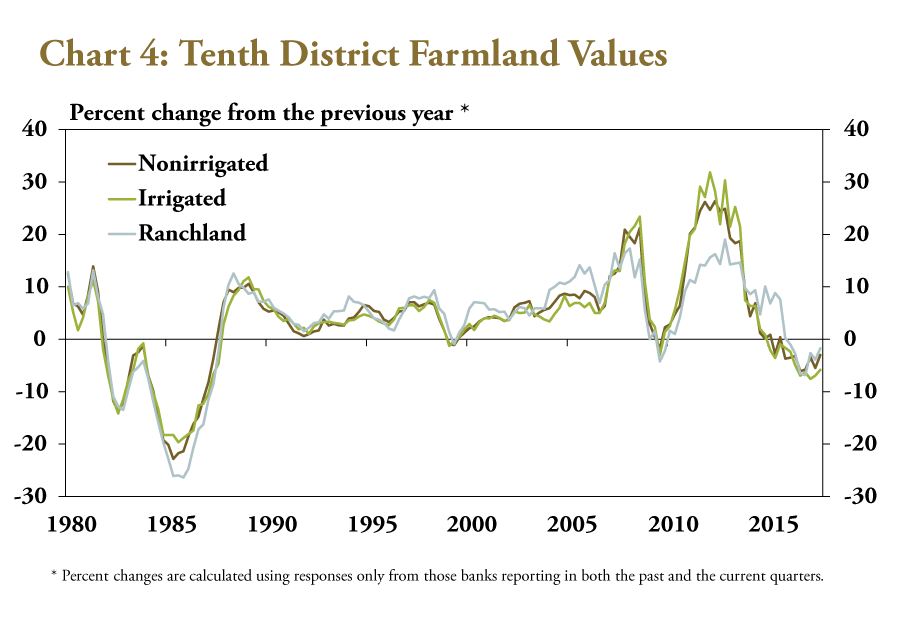

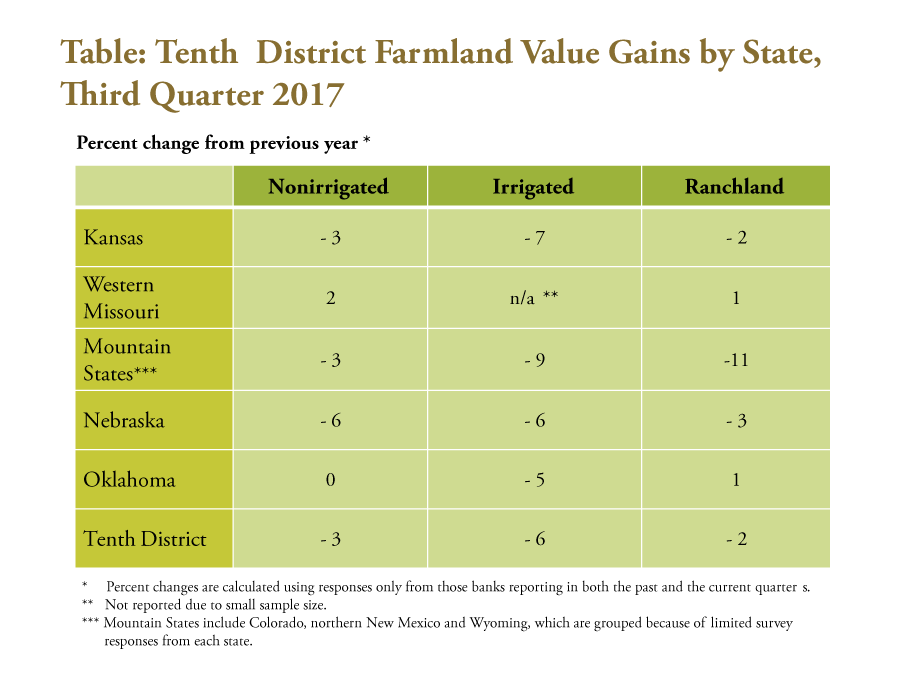

Prolonged declines in farm income also continued to push farmland values lower, but at a modest pace. For example, the value of nonirrigated and irrigated cropland declined 3 percent and 6 percent, respectively, from the previous year (Chart 4). Although the magnitudes of recent declines have yet to approach the magnitudes of the 1980s, the duration of the recent downturn in cropland values has approached that of the 1980s. The value of ranchland also continued to soften in the third quarter at a modest pace.

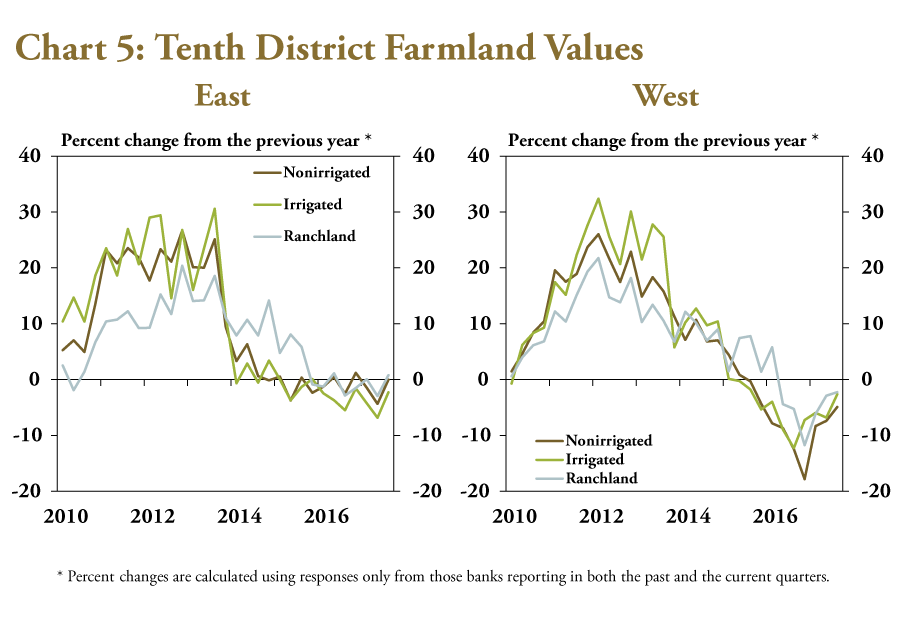

Consistent with recent surveys, farmland values in the western third of the District continued to decrease at a slightly faster pace than in the east. The value of nonirrigated cropland in the western portion of the District decreased 5 percent in the third quarter, whereas values in the eastern portion were unchanged from a year ago (Chart 5). Although the pace of declines in the western portion of the District continued to moderate, the ongoing divergence between the two regions has remained, primarily due to production potential and differences in commodity concentrations.

Changes in farmland values also differed across District states. The value of farmland in western Missouri and Oklahoma generally increased in contrast to other District states (Table). In addition, similar to recent developments in farm income, the pace of declines in farmland values also has softened throughout the District and in most states individually.

Credit Conditions and Lending Environment

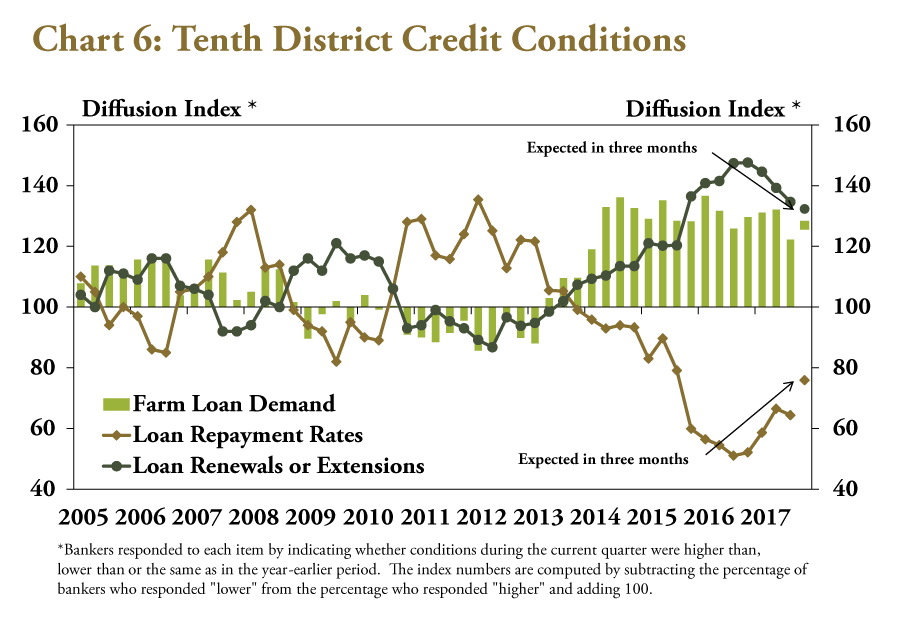

Agricultural credit conditions also tightened alongside lower farm income and farmland values. Farm loan repayment rates declined for the 16th consecutive quarter, indicative of the prolonged downturn in the District’s farm economy. In a similar vein, demand for farm loans and loan renewals and extensions continued to increase amid persistent weakness in the farm economy (Chart 6). Although bankers indicated loan demand continued to rise, the rate of increase was somewhat less than recent quarters.

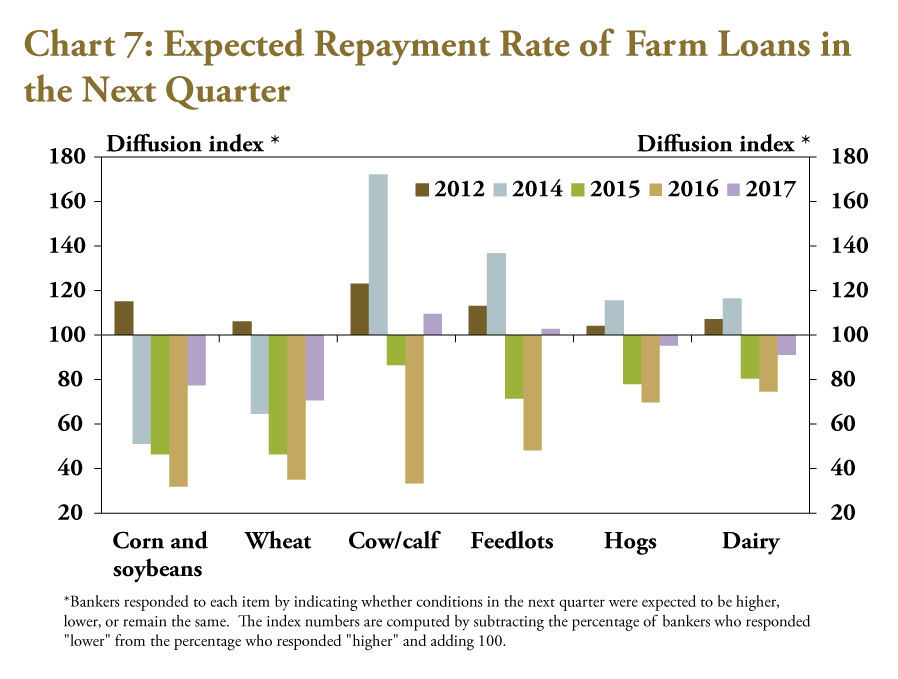

Despite the tighter credit conditions, repayment rates for some types of agricultural loans were expected to improve. For example, bankers noted that repayment rates for cattle loans were expected to improve in the next quarter (Chart 7). The expected improvement in repayment rates for cattle loans was attributed to a 4-percent increase in the price of cattle relative to a year ago. Repayment rates among producers of all other agricultural commodities were expected to decline, but at a slower pace than each of the previous three years.

The prolonged downturn in the farm economy and elevated need for loans continued to limit funding availability. In the third quarter, 12 percent of bankers reported a decrease in the funds available for financing and only 5 percent reported an increase. Reflecting ongoing tightening in agricultural credit markets, 12 percent of bankers expected a further decline in funds available for financing in the next quarter.

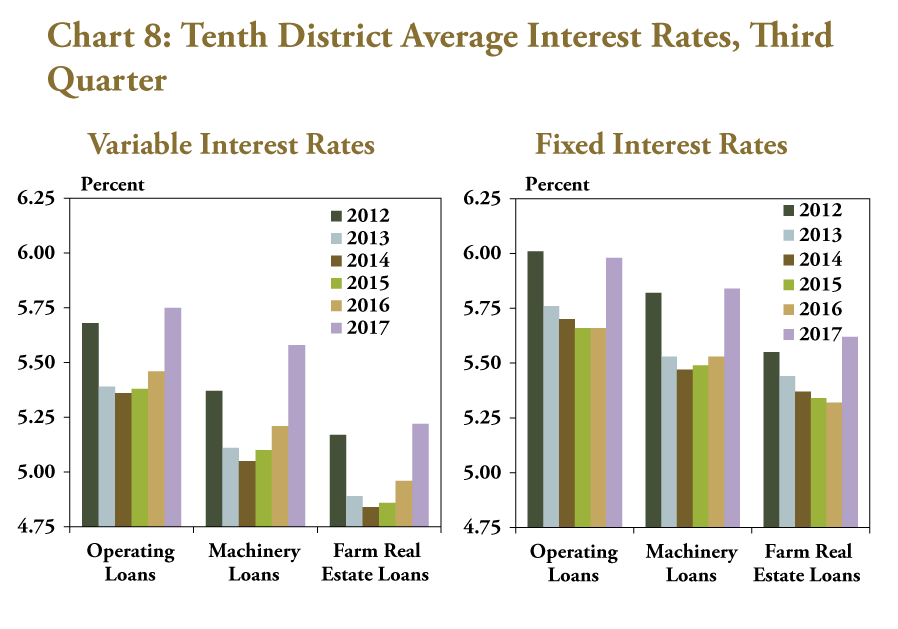

Bankers also have steadily raised interest rates on agricultural loans as credit conditions have worsened amid the prolonged downturn. In the third quarter, agricultural loans with variable interest rates increased between 26 and 37 basis points from the previous year (Chart 8). Agricultural loans with fixed interest rates increased about 30 basis points from the previous year. General changes in the broader interest rate environment also are likely to have accounted for a portion of the increase in interest rates for agricultural loans.

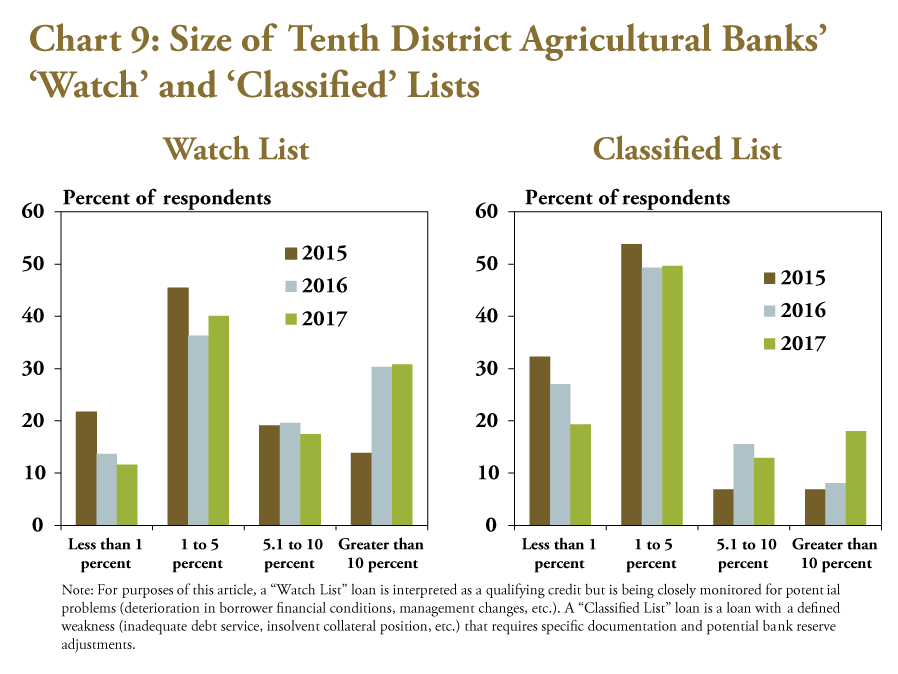

As credit conditions continued to deteriorate, bankers placed a larger share of loans on their watch and classified lists. In the third quarter, the share of bankers with more than 10 percent of their farm loans on a classified list increased sharply from a year ago (Chart 9). Likewise, the share of bankers with less than 1 percent of farm loans on a watch or classified list declined for a second consecutive year.

Although lenders continued to report increasing financial strain among their agricultural borrowers, bankers indicated that a sharp increase in the sale of farm assets was unlikely. In fact, few bankers reported that they expect more than 10 percent of their farm borrowers to sell mid-to-long-term assets, like machinery or land, by year’s end to improve cash flow or make loan payments (Chart 10). Conversely, more than 80 percent of bankers expected less than 5 percent of their farm borrowers to sell mid-to-long-term assets.

Conclusion

A prolonged downturn in the Tenth District farm economy that began several years ago persisted in the third quarter of the year. Farm income, repayment rates and farmland values declined from the previous year and were expected to decline further in the coming months. However, a larger share of bankers reported some improvement in the region’s agricultural economy. Going forward, agricultural economic conditions are still expected to remain subdued and financial stress in the farm sector may intensify further, but the sharp transition of recent years appears to be lessening.

________________________________________________________

Endnotes

-

1

According to USDA data, nearly 85 percent of Oklahoma’s cash receipts for agriculture come from cattle, hogs, broilers, eggs, milk and turkeys (the largest share in the Tenth District).

A total of 203 banks responded to the Third Quarter Survey of Agricultural Credit Conditions in the Tenth Federal Reserve District—an area that includes Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Wyoming, the northern half of New Mexico and the western third of Missouri. Please refer questions to External LinkNathan Kauffman, Omaha Branch executive or External LinkMatt Clark, assistant economist at 1-800-333-1040.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.