The past two years have been a good time for workers looking to find a job in Nebraska, but a shortage of labor in the state has constrained business activity and inflation has been an ongoing challenge. Labor shortages reached all-time highs in Nebraska in 2022, with very low unemployment and rising wages. Despite robust wage growth, inflationary pressures weighed on households and businesses in Nebraska, and a larger workforce will likely be crucial to sustaining improvements in business and economic activity in the months ahead.

Employment

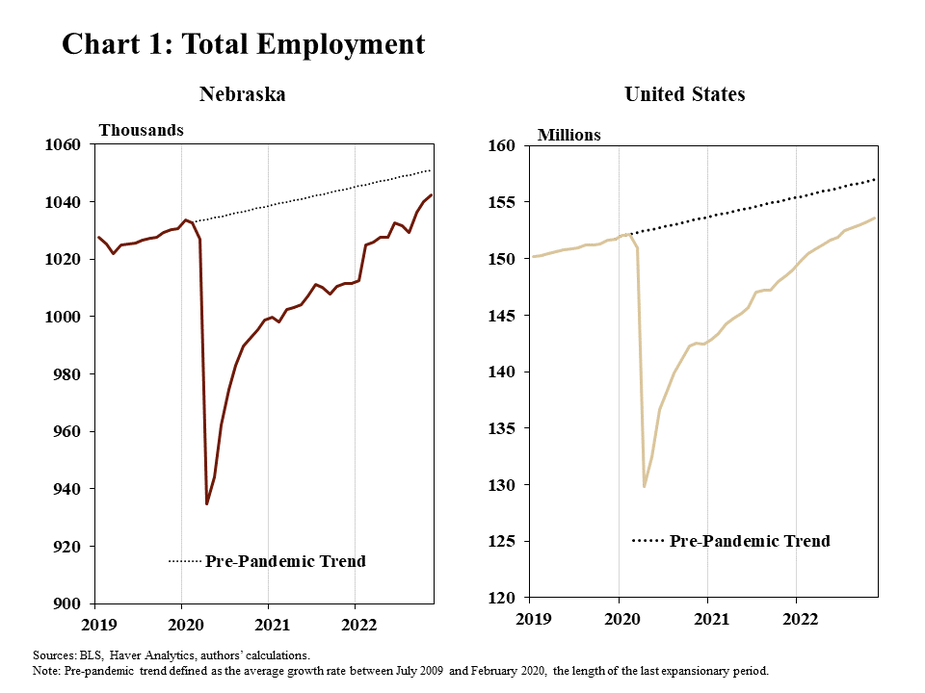

The job market in Nebraska took time to recover in the wake of the pandemic but, in recent months, the level of employment has nearly reached its pre-pandemic trajectory. As of November, employment in Nebraska was 1.1% higher than at the end of 2019 and within 0.8% of its trend over the previous decade (Chart 1). Nationally, employment reached its pre-pandemic mark slightly earlier, but remained more than 2% less than what might have been expected had job growth continued at its average pace from 2009 to 2019.

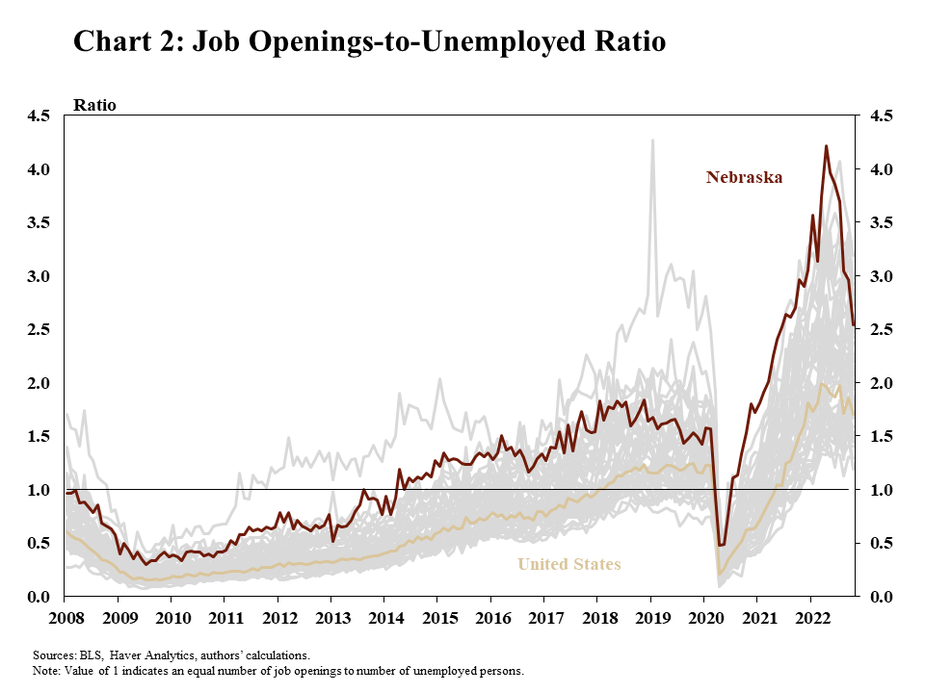

As underlying economic conditions improved through 2022, employers attempted to accelerate their pace of hiring, competing for a scarcity of workers. Midway through last year, there were more than 4 jobs available per unemployed person in Nebraska, an all-time high (Chart 2). At the time, this ratio was the highest in the nation. While the ratio of job openings-to-unemployed has since declined, Nebraska still had among the highest ratios in the country and more than 64,000 job openings as of October.

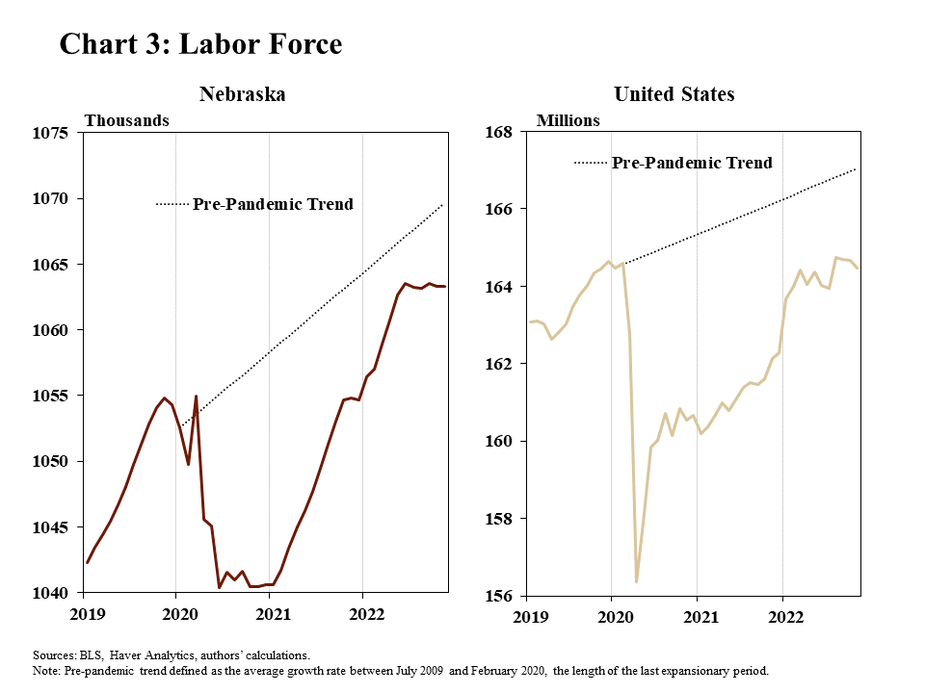

The ability to fill job openings to support business opportunities has been hindered, in part, by a lack of growth in Nebraska’s labor force. From the beginning of 2021 to mid-2022, Nebraska’s labor force expanded by 2.2% (Chart 3). Since then, however, there has been very little additional growth in the availability of labor.

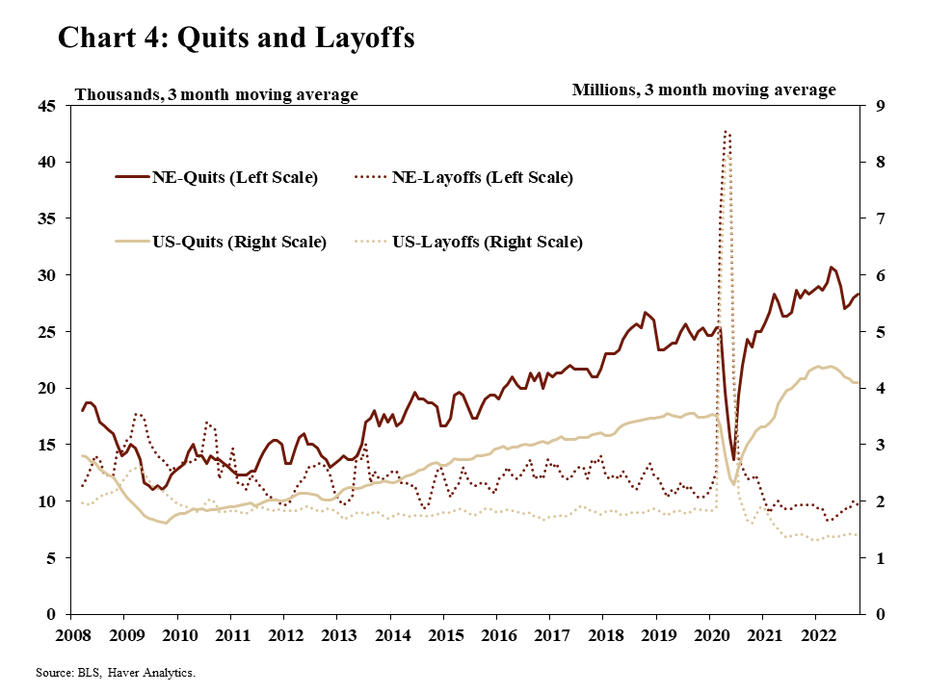

Faced with ongoing difficulties in hiring, layoffs in Nebraska have remained low and employees have increasingly left their existing job in pursuit of employment elsewhere. Quits in Nebraska reached a historic high of 30,000 last spring (Chart 4). Although an elevated quits rate and low levels of layoffs have been features of the labor market for some time, the issue has grown during the pandemic years. Between 2009 and 2019, Nebraska averaged 18,000 quits and 12,000 layoffs per month. In 2021 and 2022, the average number of monthly quits increased to 28,000 and the average number of monthly layoffs dropped to just 9,000.

Personal Income

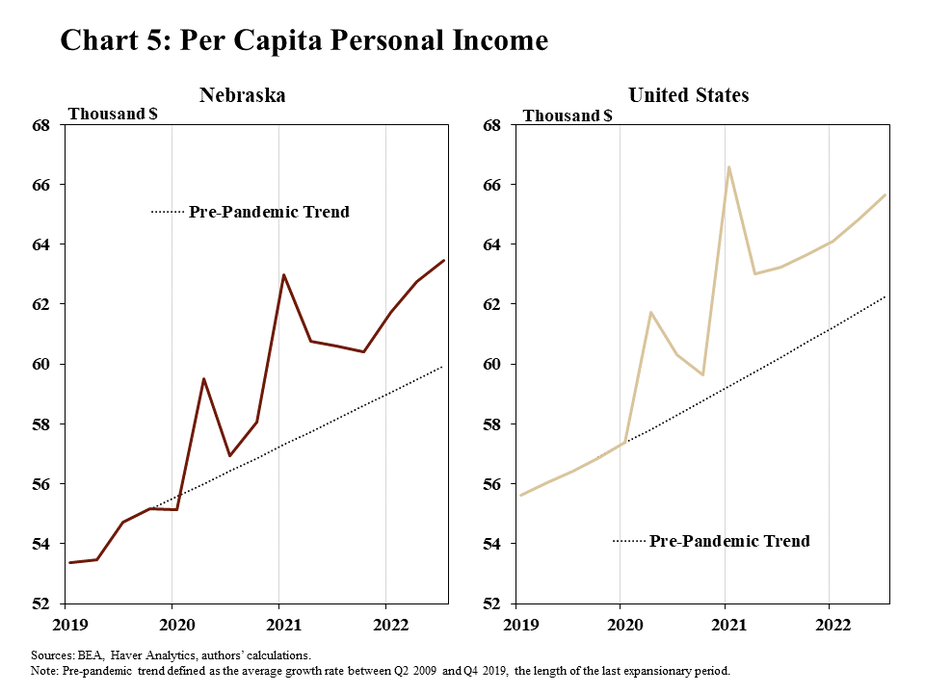

Alongside a strong labor market, incomes in Nebraska have exceeded their pre-pandemic trend. Personal income was more than 5% higher in both Nebraska and the United States than what might have been expected when applying growth rates that existed prior to 2020 (Chart 5). Federal stimulus payments to households spurred short term increases in personal income in 2020 and 2021. However, consistently faster growth in incomes has been supported by strong wage growth amid persistently tight labor markets in the months following the COVID-19 lockdowns.

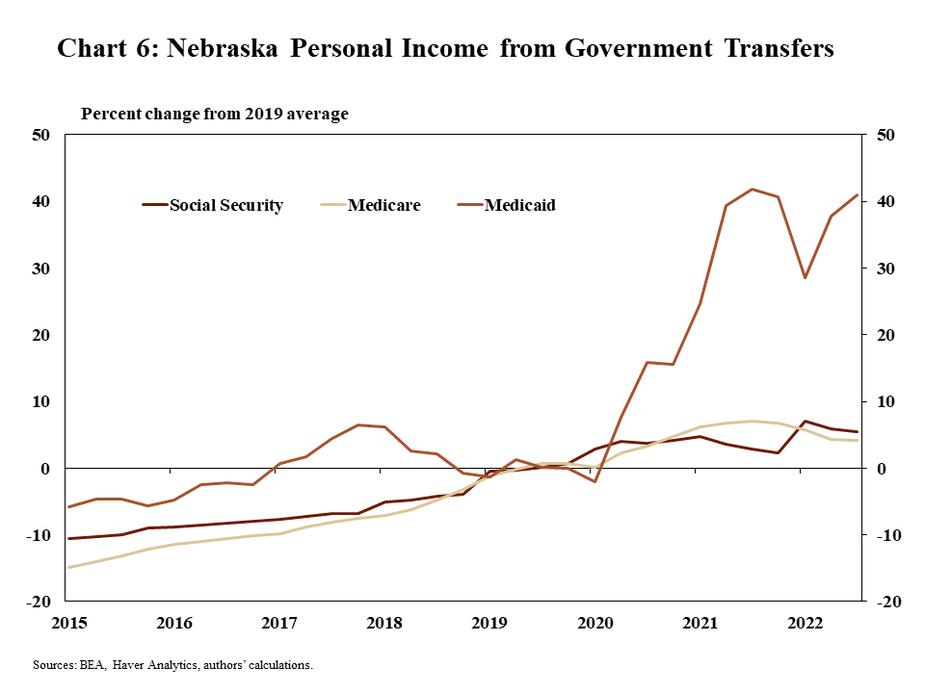

Beyond the pandemic-era stimulus payments, expansion in Medicaid payments has been one of the factors leading to increased incomes in Nebraska. Personal income in the form of Medicaid payments has increased at an average annual growth rate of 32% since expanded coverage became available in October 2020 (Chart 6). On a per capita basis, the increase in Medicaid payments translated to an increase in personal income of nearly $2,000 from 2019 to 2022.

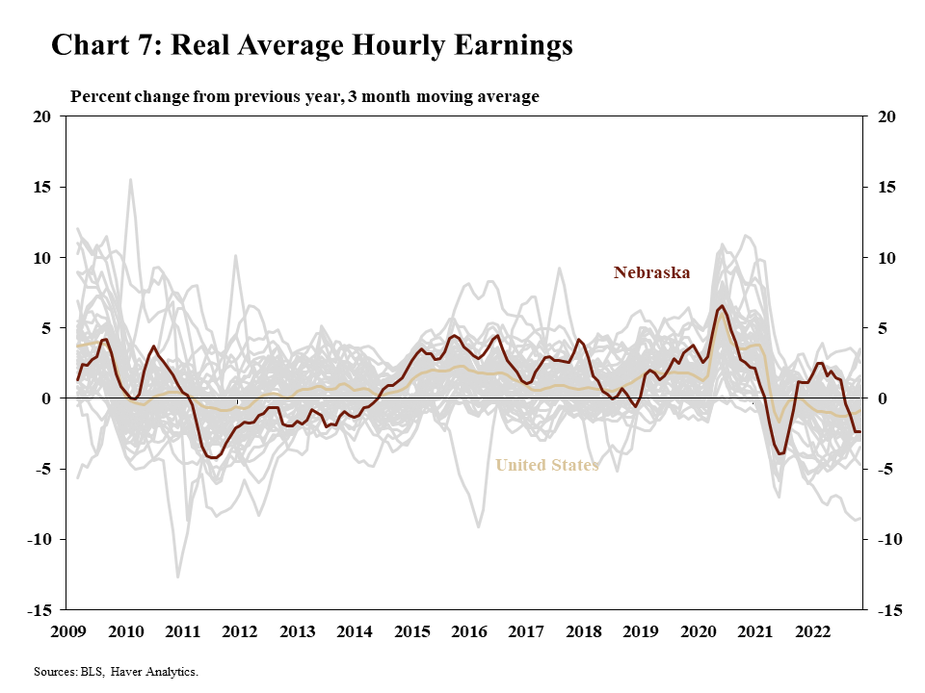

Although tight labor markets supported strong wage growth in Nebraska, as in the nation, inflation began to weigh on households more significantly in 2022. Average hourly earnings in Nebraska increased at a robust pace of 7% last year. However, in inflation-adjusted (real) terms, these earnings increased by less than 1 percent, on average, in 2022 (Chart 7). Moreover, beginning in August, hourly earnings in inflation-adjusted terms actually decreased in each subsequent month.

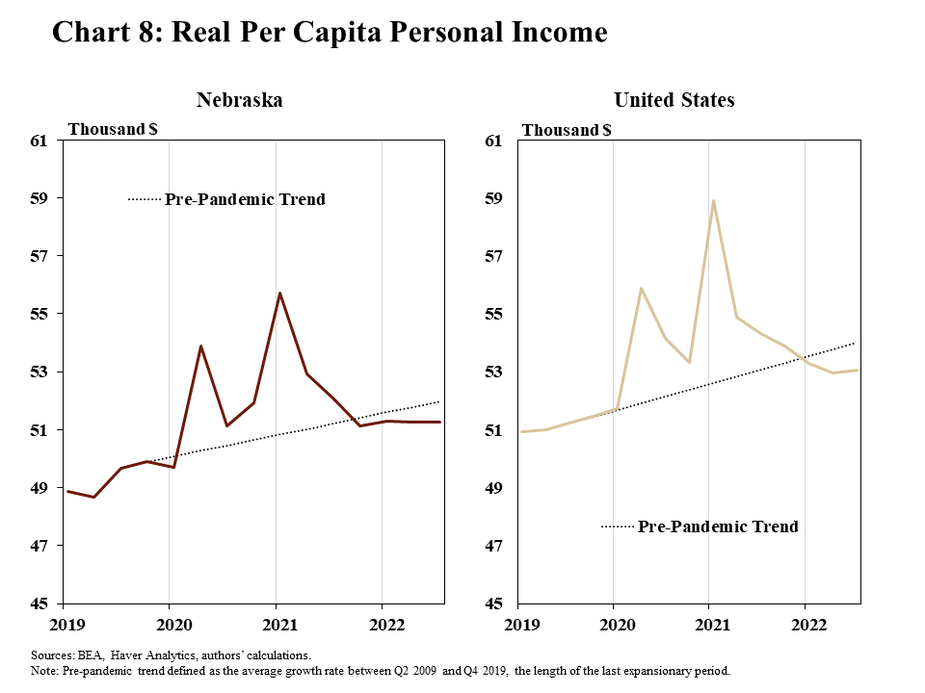

The recent decline in wages, after accounting for inflation, has also caused real incomes in Nebraska to fall below their pre-pandemic trend. While the average increase in nominal wages has been robust, the increase was less than the rate of inflation in 2022. As a result, as of the third quarter of 2022, personal income in Nebraska – in inflation-adjusted terms – was approximately 1.3% less than pre-pandemic expectations (Chart 8).

Economic Activity

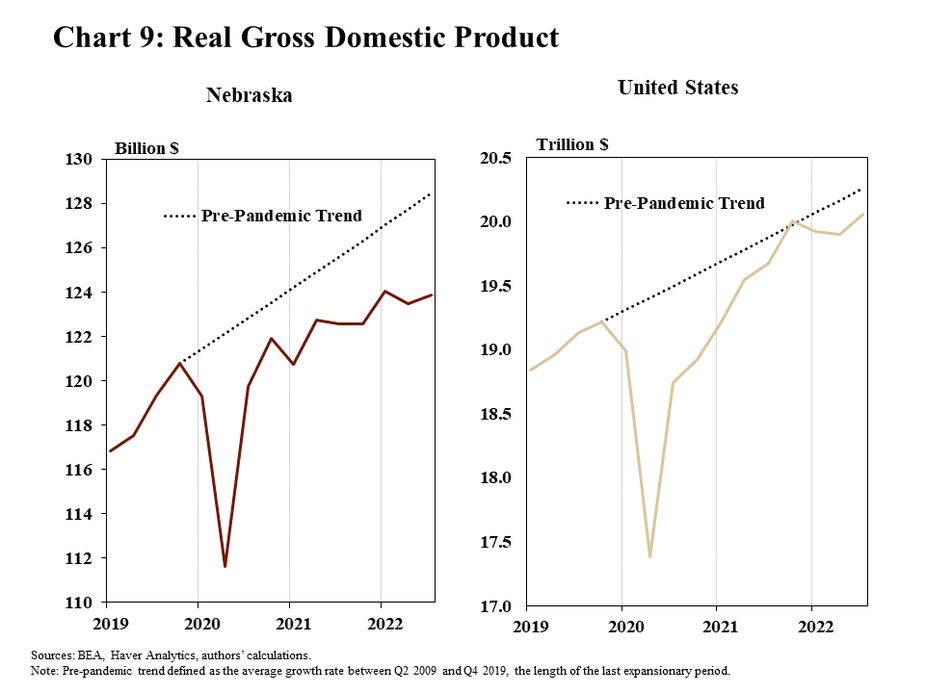

While inflation has also posed a significant challenge for businesses, a scarcity of labor likely curbed economic activity in Nebraska through 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic led to a sharp decline in real GDP of nearly 8% in just a few short months, but by October 2022 Nebraska’s economy was 2.5% larger than before the pandemic (Chart 9). Despite the recovery though, if the state’s economy would have continued expanding at its average pre-pandemic growth rate, real GDP would have been more than 6% higher last year than in 2019. In contrast, national economic activity took longer to reach pre-COVID levels but has since moved closer to its pre-pandemic path.

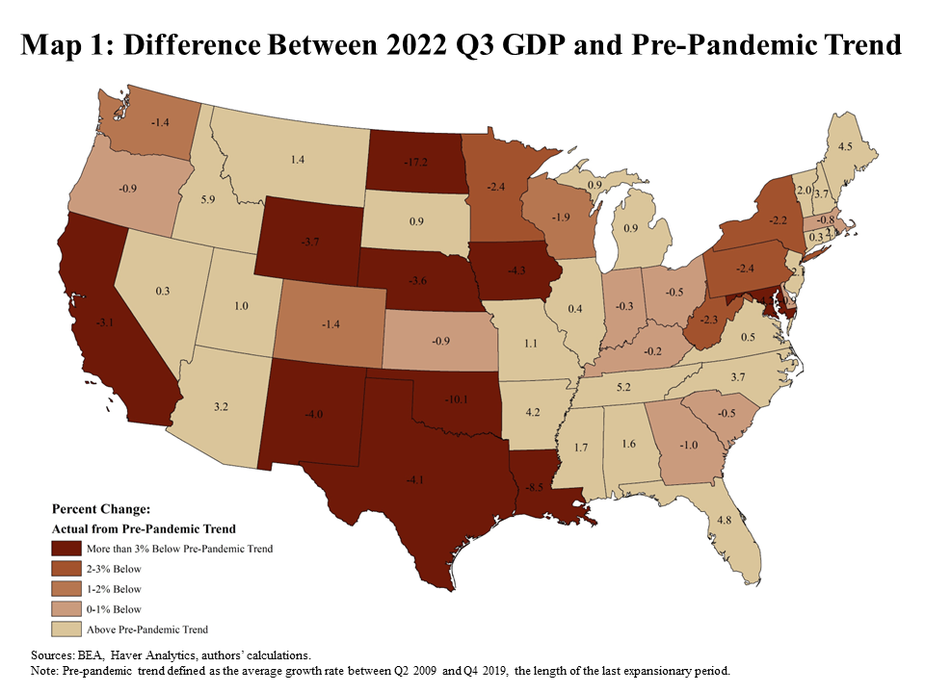

Moreover, economic output in Nebraska has been more suppressed relative to its pre-pandemic trajectory than many other states. Last year, Nebraska was one of just ten states where real GDP was more than three percentage points less than pre-pandemic expectations (Map 1). However, even though economic activity fell short of pre-COVID trends, Nebraska still fared better than several energy-producing states like Texas, North Dakota, and Louisiana.

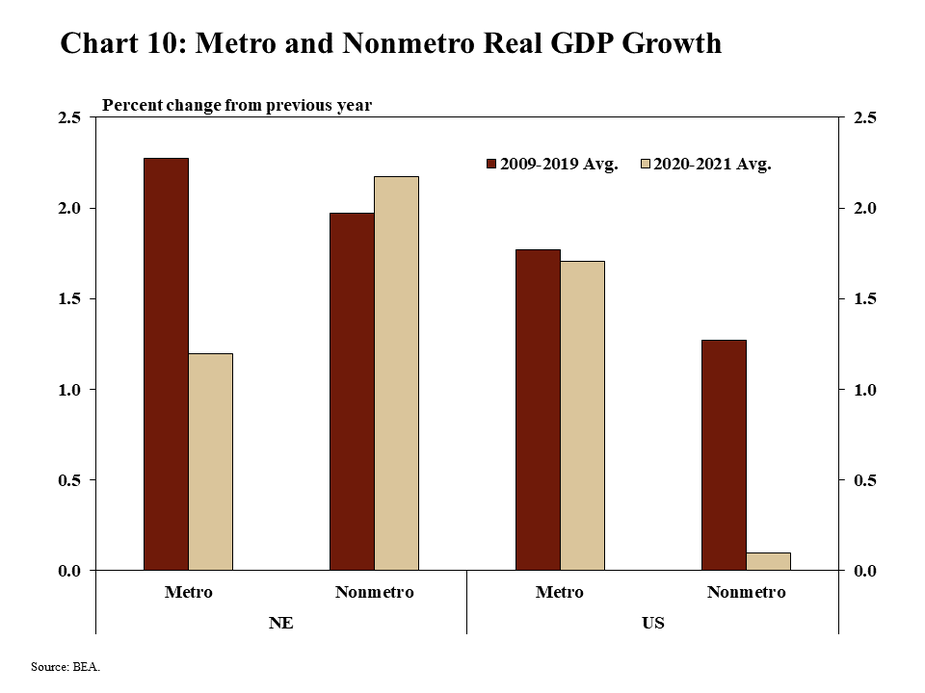

Slower economic growth in Nebraska’s metropolitan areas during the pandemic has weighed on statewide activity. Through the pandemic, Nebraska’s GDP was supported by faster economic growth in the state’s rural areas when compared to the nation. The average rate of growth in the Omaha, Lincoln and Grand Island areas, however, was a full percentage point lower in 2020 and 2021 than in the decade prior to the pandemic (Chart 10). In contrast, activity in other metros across the country expanded during the pandemic at a rate very similar to the previous decade.

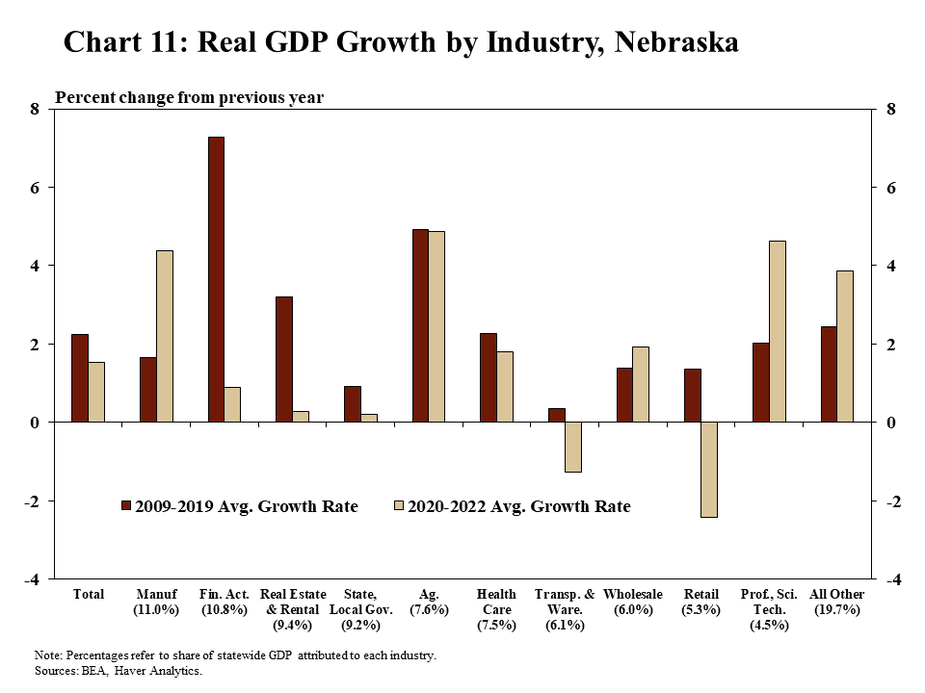

More specifically, sluggish growth in a few industries limited economic gains in Nebraska’s urban areas over the past two years. Growth in large industries like financial activities, state and local government, and real estate slowed dramatically after the emergence of COVID-19 (Chart 11). As these industries are more prominent in urban areas, overall economic growth was weaker in Nebraska’s cities. Furthermore, economic output in these industries across all U.S. metros grew at a similar or slightly faster pace, contributing to the gap between Nebraska and U.S. urban areas.

Conclusion

In addition to difficulties associated with inflation, a scarcity of labor remains one of the most notable challenges for Nebraska’s economy in 2023. Though economic output expanded in the state in 2022, a larger workforce could provide stronger support for increased economic activity in the year ahead. Based on recent trends, however, it appears that labor availability may remain limited in 2023, with potential implications for economic growth as well.