The scale of homelessness tends to be hidden because most people counted as experiencing homelessness are, in a sense, invisible. Most are sheltered in temporary and emergency shelters. Many more uncounted people experiencing (near) homelessness are either at risk of losing their homes or are doubled up with friends or family. When people experiencing homelessness are living on the street, they become more visible and tend to garner negative attention. People notice rising numbers of encampments and people sleeping on sidewalks.

While some efforts have focused on reducing health and safety issues associated with living on the street through encampment sweeps, they merely push the problem around. Encampment sweeps have rarely been coupled with housing placement, as would be done under a Housing First model for addressing homelessness. The Housing First approach ensures a person in need receives safe, secure, affordable and permanent housing before working on other issues like employment or health._

This article looks briefly at the state of homelessness across the Tenth District and the effects of Housing First policies, increasingly used as a permanent solution to homelessness.

Encampment sweeps reduce visibility but not the amount of homelessness

Even though encampment sweeps address some of the issues related to the visibility of people experiencing homelessness, the tactic in isolation does not address the underlying issues around the persistence of homelessness. Still, numerous jurisdictions across the Tenth District have proposed increased enforcement of urban camping rules for reasons of public safety, health, and sanitation. The Tenth District includes Colorado, Kansas, western Missouri, Nebraska, northern New Mexico, Oklahoma and Wyoming.

- In Missouri, a law went into effect January 1, 2023, that criminalized sleeping on state-owned property and requires jurisdictions to move campers to temporary camps. The law also prohibits jurisdictions from spending some state and federal grant dollars on permanent housing. Instead, they must spend it on temporary housing and substance abuse and mental health treatment.

- The City of Lawrence, Kansas, recently evicted the people from the homeless encampment the city supported in North Lawrence.

- Denver, Colorado, implemented a public camping ban in 2012 which led to increased use of homeless camp sweeps and ultimately a legal settlement requiring the city to give at least seven days’ notice of a sweep. In response to public pressure to treat people experiencing homelessness with humanity, Denver began combining encampment sweeps with a Housing First lens.

Homelessness has increased, but so has the availability of permanent housing

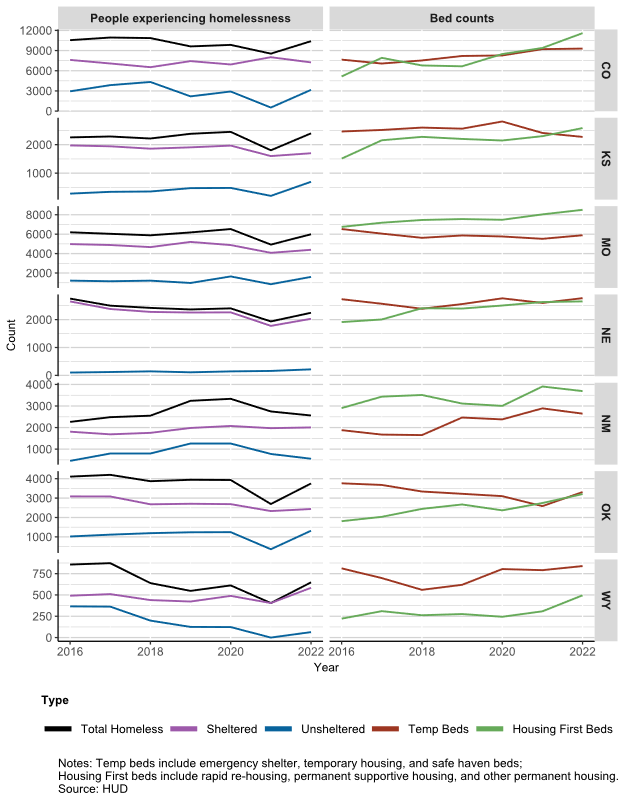

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development released the 2022 “point-in-time” homeless count data in December._ Across the District, homeless counts increased 21% since 2021 (Chart 1), driven by an increase in unsheltered homeless populations. Homeless counts have mostly returned to or have exceeded pre-pandemic levels from 2019. While the pandemic brought about expectations of increased homelessness counts, federal, state, and local aid directed to helping people’s housing situation led to a substantial drop in homelessness. As that money runs out, people are returning to a state of homelessness. New Mexico was the only state in the Tenth District to experience a continued decline in homelessness, with a 7% reduction last year and 21% since 2019.

Temporary bed_ counts largely kept pace with changing overall homeless levels. Permanent housing counts that would support Housing First policies continued to increase (12% last year, and 32% since 2019)._ Temporary beds are an indicator of whether a community has enough places for homeless populations to sleep temporarily, while permanent housing beds are preventing and ending homelessness. As such, permanent beds do not correlate with rates of homelessness like temporary beds. So, while permanent housing counts have increased, it may be masking what otherwise may have been an increase in people experiencing homelessness.

Although it appears that there are enough temporary shelter beds at the state level to shelter unsheltered homeless populations, state level estimates may hide localized mismatches between availability and need. Additionally, many temporary housing sites have restrictive policies that exclude many people experiencing homelessness or come with long waits for non-guaranteed beds that further dissuade people from using them. In many cases, unsheltered people experiencing homelessness feel safer and more comfortable sleeping on the street or in an encampment and taking their chances with weather, personal security, and policing._

Chart 1 Counts of people experiencing homelessness and bed numbers by Tenth District state

Housing First has garnered attention for reducing homelessness

Given the persistence of homelessness, it is important to look at policies that may address the underlying problem: people needing homes. Housing First policies captured a lot of attention last year, particularly due to the success Houston, Texas, experienced with its program.

Houston implemented Housing First policies with a strong emphasis on connecting organizations and data to better serve homeless populations. Officials also supported permanent housing solutions over spending money on temporary housing._ Of note, Houston moved more than 25,000 homeless people into permanent housing over the last decade, cutting the number of people in the city experiencing homelessness by 63%. Rather than sweep encampments and push homeless people to temporary housing or another encampment, Houston organizations only dismantled encampments if they had guaranteed permanent housing for everyone in the camp.

External LinkResearch by Elior Cohen of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City finds that Housing First programs led to similar reductions in homelessness in Los Angeles. Cohen found that homeless populations provided with a more permanent housing solution reduced their incidents with police, increased their income and employment and reduced future interactions with homeless services.

Los Angeles Housing First program recipients:

- Were 23% less likely to return to homeless support services within 18 months and 15% less likely over 30 months.

- Reduced their probability of being in jail by 95% and reduced by 85% their probability of receiving a criminal charge.

- Increased their probability of reporting at least some income by 23%.

The study found no increase in usage of health services. Housing First program costs were offset by savings within 18 months.

Cohen’s research also looked at program design, including short-term versus long-term solutions, placement strategies and differences in success rates based on caseworker Housing First placement rates. All the results are too much for this article, but worth External Linkchecking out or reaching out to Dr. Cohen for more information.

Within the Tenth District, Denver has experimented with using social impact bonds to finance a Housing First program. Denver’s program was focused on breaking the homelessness-jail cycle among those who were chronically homeless and who had frequent interactions with the criminal justice and emergency health care systems. The Urban Institute and University of Colorado-Denver researchers evaluated the program._

Findings from Denver after three years of housing placement:

- 77% of recipients remained in stable housing.

- Shelter visits reduced by 40% and shelter stays by 35%.

- Police interactions reduced by 34% and arrests by 40%.

- Emergency department visits dropped by 40%.

- Office-based health care visits with a psychiatric diagnosis increased by 155% and unique prescription medications increased by 29%.

- Use of short-term detoxification facilities dropped by 65%.

About half of the per-person cost of the supportive housing program was offset by costs that were avoided, such as jail and emergency department visits.

Is a Housing First model right for your jurisdiction?

While Housing First programs may be difficult for jurisdictions to implement given the additional upfront costs, research presented shows that the savings to public program use can offset those costs over time. This is in part because recipients of Housing First placements find stability. They have a place to call home and don’t have to worry about where they’re sleeping each night. And the livelihood benefits they receive from stable housing set them up for longer-term success. Even still, a major challenge remains in how budgets are structured and the difficulties of shifting money from one pot to another, especially when costs and savings do not occur simultaneously. While Denver approached this initially with a Social Impact Bond, few places are likely to find generous donors to fund such an initiative or continue to fund it beyond the initial stage. As federal and state policies change, there are likely to be additional opportunities and challenges. As such, the Housing First model may be worth exploring for your jurisdiction.

Endnotes

-

1

HUD has a policy brief covering Housing First available here: External Linkhttps://www.hudexchange.info/resource/3892/housing-first-in-permanent-supportive-housing-brief/

-

2

Point-in-time counts are conducted in January each year. Homeless populations fluctuate throughout the year, but this is the only census of homeless population totals.

-

3

Temporary beds include emergency shelter, temporary housing, and safe-haven beds.

-

4

Housing first beds include those for rapid rehousing, permanently supportive housing, or other permanent housing.

-

5

Herring, Chris. “Between street and shelter: Seclusion, exclusion, and the neutralization of poverty.” Class, ethnicity and state in the polarized metropolis: Putting Wacquant to work (2019): 281-305.

-

6

A number of news articles were written last year highlighting Houston’s program, for an example of the coverage, see: External Linkhttps://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/14/headway/houston-homeless-people.html; External Linkhttps://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/houston-data-housing-first-homeless-strategy-homelessness/640496/

-

7

External Linkhttps://www.urban.org/features/housing-first-breaks-homelessness-jail-cycle